Spasticity is defined as “velocity-dependent increase in muscle tone” and can be observed in many neurological disorders. Spasticity after a spinal cord injury is found in more than 60% of the patients. Spinal cord motor neurons become highly sensitive to the residual signals passing through the spinal cord and result in abnormal and consistent muscle contractions. In this article, we will take a closer look at defining spasticity, what it means to have spasticity after a severe spinal cord trauma and the common ways to tackle spasticity, including epidural stimulation treatment.

Definition: Spasticity is persistently increased muscle tone caused by over-stimulation of stretch reflex after a spinal cord injury. There are important anatomical and physiological hallmarks involved in producing spasticity. Let's take a closer look.

Defining Spasticity: What is it and what causes it?

Spasticity is caused by over-stimulation of stretch reflex after a spinal cord injury. This leads to persistently increased muscle tone. When we are defining spasticity and trying to understand it, we must first understand two important anatomical and physiological hallmarks: The human motor system and how Stretch reflexes work. Let’s take a closer look.

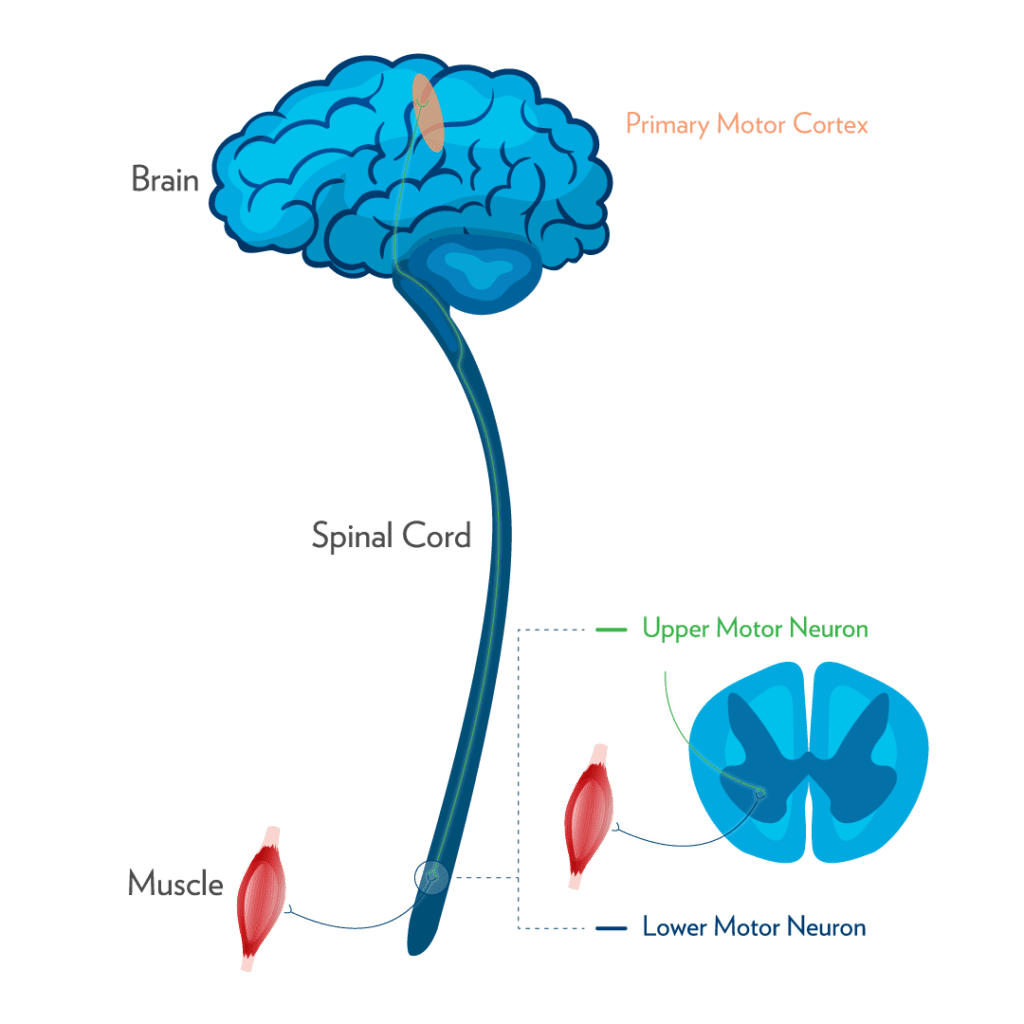

Human Motor System

Our motor system consists of two distinct types of motor neurons – upper and lower motor neurons. Upper motor neurons originate from the brain’s motor cortex. Their nerve fibers, or ‘axons’, extend all the way down through the brainstem, which connects the brain with the spinal cord, and the spinal cord itself. Upper motor neurons communicate with a second line of neurons, called lower motor neurons. The cells bodies of lower motor neurons reside, primarily, in the brain stem cells and the spinal cord and their axons leave the brainstem and/or the spinal cord in the form of either cranial or spinal nerves, which provide nerves supply to various muscle groups.

Stretch Reflex

The Stretch reflex is a muscle contraction, which occurs when a particular muscle is stretched. Our brain is responsible for the regulation of stretch reflex, through a process called “Supraspinal Input”. This takes place through the upper motor neuron pathways. In a normally functioning spinal cord, there is a proper regulation of the stretch reflex and hence we have very regular muscle tone in our muscles.

Spasticity After a Spinal Cord Injury

Initial post injury state

After a spinal cord injury, there is disruption of the upper motor neuron pathways which results in irregulation of the stretch reflex. Once the communication channels (upper motor neuron pathways) are disrupted, there is decreased or abnormal “supraspinal input”. This in turn forces the lower motor neurons to become super sensitive to residual input from the upper motor neurons. It makes the muscles stretch abnormally and randomly, producing spasms.

Acute spinal cord injury results in what is termed as “spinal shock”. The spinal cord essentially shuts down as a result of severe trauma. This results in complete loss of communication between the brain and the lower segments of the spinal cord, below the level of injury. This condition may persist from between 24 hours to a few weeks. During this period patients normally do not have any muscle tone or contractions. This state is called “flaccid paraplegia”.

The Beginnings of Spasticity

After this initial period of spinal shock, the surviving spinal pathways “wake up” and try to communicate with the lower motor neurons located below the level of injury. The previous disruption of these pathways means that this communication is often abnormal. The result is increased excitability of the lower motor neurons, producing abnormal and persistent muscle contractions.

The spinal cord retains a certain level of capacity to regenerate itself after spinal cord injury even when the injury is initially termed as “complete”. Therefore, neuroplasticity allows upper motor neuron pathways to regenerate over time. In many patients with a complete spinal cord injury there is initially no spasticity because the lower motor neurons can not receive any input from the brain. However, the regeneration of upper motor neuron pathways over time results in increased communication with the lower motor neurons. This causes the lower motor neurons to start producing these abnormal and persistent muscle contractions. Therefore, spasticity is an inevitable consequence of the regeneration of the spinal cord after a severe trauma.

How we treat spasticity

Spasticity is an important factor in maintaining muscle mass and bone density after a spinal cord injury. However excessive spasticity can also result in postural instability and skeletal deformities. Therefore, the most important consideration for the management of spasticity is to keep a balance between its usefulness and its detrimental effects. Generally speaking, there is no single definite option for the management of spasticity in all spinal cord injury patients. The approach in each case, however, should be systemic. Most conservative options such as physical rehabilitation, and oral antispasmodics should be considered before aggressive pharmacological (Baclofen Pump) and surgical options. Many patients find regular physical rehabilitation combined with oral baclofen useful in managing the spasticity.

In general, if spasticity is manageable, it should not necessarily be considered as a complication. In many individuals with SCI, spasticity is the first step towards volitional muscle control. At Verita Neuro, we have observed increased levels of spasticity in the majority of the patients after the initial treatment, indicating a successful transition towards a more incomplete injury. The excessive spasticity, however, can be tackled using epidural spinal cord stimulation. Epidural stimulation can be used to regulate the over-excitability of upper and lower motor neurons in spinal cord injury patients. We have noticed many of our patients see an initial increase in levels of spasticity but the long term use of the stimulation also helps in managing excessive stimulation.

References

- Adams MM, Hicks AL. Spasticity after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2005 Oct;43(10):577-86.

- Sina Sangari, PhD, et al. Residual Descending Motor Pathways Influence Spasticity after Spinal Cord Injury.

- Lance JW. The control of muscle tone, reflexes, and movement: Robert Wartenberg Lecture. Neurology 1980;30:1303–1313. [PubMed: 7192811]

- Bennett DJ, Li Y, Harvey PJ, Gorassini M. Evidence for plateau potentials in tail motoneurons of awake chronic spinal rats with spasticity. J Neurophysiol 2001;86:1972–1982. [PubMed: 11600654]

- Li Y, Bennett DJ. Persistent sodium and calcium currents cause plateau potentials in motoneurons of chronic spinal rats. J Neurophysiol 2003;90:857–869. [PubMed: 12724367]

- Kirshblum S. Treatment alternatives for spinal cord injury related spasticity. J Spinal Cord Med 1999; 22: 199–217.

- Gracies JM, Elovic E, McGuire J, Simpson DM. Traditional pharmacological treatments for spasticity. Part I: Local treatments. Muscle Nerve Suppl 1997; 6: S61–S91.

- Gracies JM, Nance P, Elovic E, McGuire J, Simpson DM. Traditional pharmacological treatments for spasticity. Part II: General and regional treatments. Muscle Nerve Suppl 1997; 6: S92–120